February 2024

Creation's Proclamation

23/02/24 16:51

There’s an old joke about a burley backwoodsman who applied for a job as a lumberjack, claiming to be the fastest axman alive. When the boss asked the calloused codger where he might have gained the experience necessary to do such a job, he responded that he worked for years as the lead cutter in the Sahara Forest. The boss, taken aback, inquired, “Are you talking about the Sahara Desert?” The boastful logger replied, “Yeah. That’s what they call it now.”

That same lumberjack must have also worked on the Orkney Islands. This curious archipelago off the north coast of mainland Scotland is almost totally void of forestation. In fact, there is a landmark on Albert Street in the town of Kirkwall known as “The Big Tree.” It’s a sacred 200-year-old sycamore that’s kept erect by a metal rod through its hollow trunk — an attempt to preserve it for future generations.

But even without woodlands, somehow these 70 separate islands — only 20 inhabited — come together to offer a peculiar beauty that promises to send pensive viewers into a melancholy state. Chartreuse hills tumble into inky peat bogs then rise again and climb to the overcast horizon. Now and then, brilliant sunbeams break through the steely skies to shine on countless sheep, grazing wherever they please. Ancient stone fences cordon off long-abandoned cottages made of matching material. The population today lives in newer farm compounds — cottages, barns and outbuildings clustered together in a way that when viewed from a distance look like wee kingdoms on a Carcassonne game board.

In the Orkneys, a coastline of some kind is seldom out of sight: off to the east, a sheer 300-meter cliff with angry waves beating its base; out to the west, a white-sand beach with rows of imbedded black strata temporarily holding back the tide. These settings are replete with winged wildlife as the Orkneys are home to the United Kingdom’s largest colonies of seabirds, which, when they’re not nesting, continuously glide and squawk aloft. Yet the dominant sound is always the howling wind from the North Sea. And that’s why the locals say they are treeless: salt air and constant gales.

But behind this desolate façade lurks some of Europe’s greatest mysteries. Roughly a half century before the first blocks were set in place at the Pyramids of Giza, a thriving colony existed on the Orkneys. Perfectly preserved under sand until 1850, Skara Brea now provides a pristine example of what life was like on these low-lying islands 3,000 years before Christ. Who these people were, how they got to these isolated islands, and where they went still has archeologists guessing.

Then there’s the nearby Ring of Brodgar, the third largest stone circle in the British Isles. Thirty-six of the original 60 stone slabs still stand. How it ties into the Skara Brea's culture remains a subject of debate between Neolithic historians. Was it a rudimentary astrological observatory or perhaps a temple? (Some archeologists think the Ring of Brodgar may have been a shrine for sun worship while the neighboring Stones of Stenness was a place to pay homage to the moon.)

Dozens of stone circles, chambered tombs, and burial mounds are scattered throughout the islands. Other settlement sites also exist — some with rudimentary indoor toilets! More are undoubtedly waiting to be discovered.

Nick Card, professor at the University of the Highlands and the director of excavations on the Orkney Islands, has written, “London may be the cultural hub of Britain today, but 5,000 years ago, Orkney was the centre for innovation for the British Isles. Ideas spread from this place. The first grooved pottery, which is so distinctive of the era, was made here, for example, and the first henges – stone rings with ditches round them – were erected on Orkney. Then the ideas spread to the rest of the Neolithic Britain. This was the font for new thinking at the time.”

As Judi and I explored these places — essentially having them to ourselves — we talked about what life would have been like for these people whose primary focus was to hunt, fish, and farm in order to survive another day. Did they have any inkling that the world was round and that there was a myriad of more-hospitable places to live?

We also talked about what might have been their concept of the Creator and whether their rituals around the stone rings might have left room for the God of the Bible. To ponder this exposes the possibility of divine subjectivity and the complexity of holy grace. Did these people have a sufficiently appropriate faith-response to God’s revelation through creation and to that which He placed in their hearts? Instead of thinking as the Ring of Brodgar and the Stones of Stenness as evil places of pagan ritual, perhaps they were constructed in an attempt to respond — the only way the Skara Brea people knew how — to that which was intrinsic and to reach out to a God whose name they never heard uttered.

“For ever since the world was created, people have seen the earth and sky. Through everything God made, they can clearly see his invisible qualities — his eternal power and divine nature” (Romans 1:20, NLT). And when those “who have never heard of God’s law follow it more or less by instinct, they confirm its truth by their obedience. They show that God’s law is not something alien, imposed on us from without, but woven into the very fabric of our creation. There is something deep within them that echoes God’s yes and no, right and wrong. Their response to God’s yes and no will become public knowledge on the day God makes his final decision about every man and woman” (Romans 2:15-16, The Message).

It’s likely that Paul in Athens was talking about people like those from Skara Brea when he said, “… we should not think that the divine being is like gold or silver or stone—an image made by human design and skill. In the past God overlooked such ignorance, but now he commands all people everywhere to repent” (Acts 17:29-30, NIV).

If God’s grace and mercy is applied as I trust it might be, maybe in heaven we’ll not only be able to coax Noah to describe his feelings when the first raindrops fell or inquire of Peter what it was like to walk on water, but also ask someone from Skara Brea who first came up with the idea of indoor plumbing.

That same lumberjack must have also worked on the Orkney Islands. This curious archipelago off the north coast of mainland Scotland is almost totally void of forestation. In fact, there is a landmark on Albert Street in the town of Kirkwall known as “The Big Tree.” It’s a sacred 200-year-old sycamore that’s kept erect by a metal rod through its hollow trunk — an attempt to preserve it for future generations.

But even without woodlands, somehow these 70 separate islands — only 20 inhabited — come together to offer a peculiar beauty that promises to send pensive viewers into a melancholy state. Chartreuse hills tumble into inky peat bogs then rise again and climb to the overcast horizon. Now and then, brilliant sunbeams break through the steely skies to shine on countless sheep, grazing wherever they please. Ancient stone fences cordon off long-abandoned cottages made of matching material. The population today lives in newer farm compounds — cottages, barns and outbuildings clustered together in a way that when viewed from a distance look like wee kingdoms on a Carcassonne game board.

In the Orkneys, a coastline of some kind is seldom out of sight: off to the east, a sheer 300-meter cliff with angry waves beating its base; out to the west, a white-sand beach with rows of imbedded black strata temporarily holding back the tide. These settings are replete with winged wildlife as the Orkneys are home to the United Kingdom’s largest colonies of seabirds, which, when they’re not nesting, continuously glide and squawk aloft. Yet the dominant sound is always the howling wind from the North Sea. And that’s why the locals say they are treeless: salt air and constant gales.

But behind this desolate façade lurks some of Europe’s greatest mysteries. Roughly a half century before the first blocks were set in place at the Pyramids of Giza, a thriving colony existed on the Orkneys. Perfectly preserved under sand until 1850, Skara Brea now provides a pristine example of what life was like on these low-lying islands 3,000 years before Christ. Who these people were, how they got to these isolated islands, and where they went still has archeologists guessing.

Then there’s the nearby Ring of Brodgar, the third largest stone circle in the British Isles. Thirty-six of the original 60 stone slabs still stand. How it ties into the Skara Brea's culture remains a subject of debate between Neolithic historians. Was it a rudimentary astrological observatory or perhaps a temple? (Some archeologists think the Ring of Brodgar may have been a shrine for sun worship while the neighboring Stones of Stenness was a place to pay homage to the moon.)

Dozens of stone circles, chambered tombs, and burial mounds are scattered throughout the islands. Other settlement sites also exist — some with rudimentary indoor toilets! More are undoubtedly waiting to be discovered.

Nick Card, professor at the University of the Highlands and the director of excavations on the Orkney Islands, has written, “London may be the cultural hub of Britain today, but 5,000 years ago, Orkney was the centre for innovation for the British Isles. Ideas spread from this place. The first grooved pottery, which is so distinctive of the era, was made here, for example, and the first henges – stone rings with ditches round them – were erected on Orkney. Then the ideas spread to the rest of the Neolithic Britain. This was the font for new thinking at the time.”

As Judi and I explored these places — essentially having them to ourselves — we talked about what life would have been like for these people whose primary focus was to hunt, fish, and farm in order to survive another day. Did they have any inkling that the world was round and that there was a myriad of more-hospitable places to live?

We also talked about what might have been their concept of the Creator and whether their rituals around the stone rings might have left room for the God of the Bible. To ponder this exposes the possibility of divine subjectivity and the complexity of holy grace. Did these people have a sufficiently appropriate faith-response to God’s revelation through creation and to that which He placed in their hearts? Instead of thinking as the Ring of Brodgar and the Stones of Stenness as evil places of pagan ritual, perhaps they were constructed in an attempt to respond — the only way the Skara Brea people knew how — to that which was intrinsic and to reach out to a God whose name they never heard uttered.

“For ever since the world was created, people have seen the earth and sky. Through everything God made, they can clearly see his invisible qualities — his eternal power and divine nature” (Romans 1:20, NLT). And when those “who have never heard of God’s law follow it more or less by instinct, they confirm its truth by their obedience. They show that God’s law is not something alien, imposed on us from without, but woven into the very fabric of our creation. There is something deep within them that echoes God’s yes and no, right and wrong. Their response to God’s yes and no will become public knowledge on the day God makes his final decision about every man and woman” (Romans 2:15-16, The Message).

It’s likely that Paul in Athens was talking about people like those from Skara Brea when he said, “… we should not think that the divine being is like gold or silver or stone—an image made by human design and skill. In the past God overlooked such ignorance, but now he commands all people everywhere to repent” (Acts 17:29-30, NIV).

If God’s grace and mercy is applied as I trust it might be, maybe in heaven we’ll not only be able to coax Noah to describe his feelings when the first raindrops fell or inquire of Peter what it was like to walk on water, but also ask someone from Skara Brea who first came up with the idea of indoor plumbing.

Just Another Foreigner

12/02/24 13:34

In any of the many tourist shops in Edinburgh, Glasgow, or Inverness, those of Scottish descent can purchase countless tartan products denoting their clan. If you’re a Stewart, Campbell, Fraser, MacDonald, MacLeod, MacKenzie, or any of the other 30 or more “Macs,” there’s a kilt, scarf, fly or tie in your personal plaid, either on the rack or in the back.

Notwithstanding, in our past visits to Scotland, we’ve never been able to find anything bearing the colors of my mother’s father’s family. They were Scotch-Irish with the surname Gillogly. On those occasions when we inquired about our kin’s woven standard, the shop clerks would always get puzzled looks on their faces and say they were unfamiliar with the name — and then refer us to another shop that had more inventory or a self-avowed genealogy expert.

Actually, we didn’t need the latter. My mother’s sister was a genealogy aficionado. Long before the days of the Internet and ancestory.com, she taught college-level courses on lineage research. By spending countless hours in libraries, courthouses, and cemeteries, she traced her father’s ancestors back to Europe in the 17th century. Thanks to her diligence, we knew when, why, and how our people journeyed from Ireland to the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia to the mountains of western Pennsylvania to the hills of southeastern Ohio. In the “old country,” they were farmers who worked the land on several islands in Lower Lough Erne, near Enniskillen, in County Fermanagh, Ulster. My fifth great-grandparents, John and Mary Jane (Moore) Gillogly were both born in Enniskillen in 1847 but died in Muskingum County Ohio, she in 1816 and he in 1855 — yes, he lived to be 108.

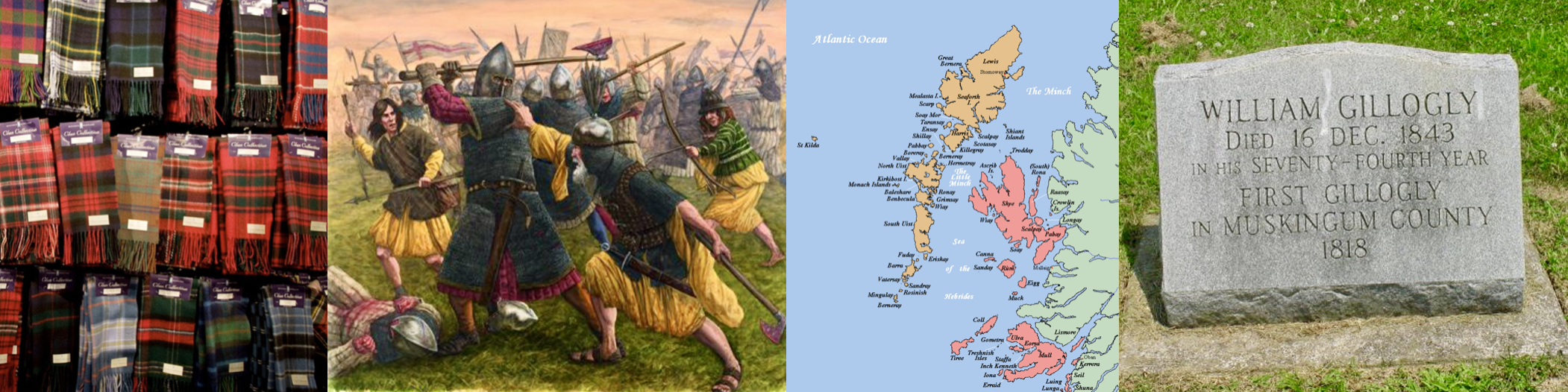

But what about the Scottish origin, and what took them to Ireland? Starting in the early 1600s, Scottish protestants living largely in Dunfries and The Borders, the southernmost parts of the country, were coerced, even forced, to leave their homes and move west across the water to populate the Plantation of Ulster so England would have a foothold in Ireland. Those peasant pawns were the first to be known as Scotch-Irish. The English plan was to confiscate all the lands of Gaelic Irish nobility and set the Scots up as farmers on those same properties. But the farmers weren’t fighters. For this plan to work, they needed enforcers. So London looked north and decided the rascally, rugged Highlanders who had been giving them fits since the days of William Wallace were who they needed to hire.

But what’s interesting is that many Highland warriors were already in Ireland — recruited hundreds of years earlier to comprise private armies for Irish chieftains. The irony is that by the 1600s, you had Highlanders protecting the Irish from Highlanders serving as soldiers for the English. Whenever my relatives got to Ireland — probably in the 1200s or 1300s — and whatever side they were on — probably the Irish — they were apparently mercenaries. As a neighbor here in Plockton told me, “Highlanders don’t need much of a reason to fight.”

But why no personalized plaid? What I recently learned was that Gillogly was an Anglicized forms of the Irish surname Galloglaigh, which was an Irish variant of the Gaelic name MacGalloglach. In Gaelic, the mac, of course, means “son of.” The gall part means “foreigner” and oglach (or owglass) means young warrior. Pushing this historical door open a bit further, it seems my Scottish ancestors were heavily armed fighters referred to as Gaelic-Norse who originally rowed over from the Skrettingland area of southeast Norway. Essentially, they were Viking marauders and plunderers who liked what they saw in Scotland and decided not to row back. But instead of being known by their family, they were known by their macabre profession, and thus there was no family crest or tartan. However, the Scottish home base for the MacGalloglach clan was the Balmartin area of North Uist in the Outer Hebrides, Scotland’s far northwestern islands. That means they would have been intermingled and probably intermarried with the Clan MacDonald who laid hold to that land early on. Now that I know, I guess the closest I’ll ever get to a Gillogly tartan, is a MacDonald hand-me-down.

In Act 1, Scene 2 of Shakespeare’s Macbeth, an unnamed wounded soldier tells King Duncan and his sons, “…the merciless Macdonwald....from the Western Isles of kerns and gallowglasses is supplied.” In other words, the MacDonalds had military might at their disposal: the Kerns, lightly armed foot soldiers who generally carried a wooden shield and a sword; and the Gallowglass (a.k.a., Galloglachs… Galloglaighs…Gilloglys), heavily armored warriors hand-picked for their strength and massive size. They were known for carrying halberds, which were battle axes on long poles. Thankfully, they eventually beat their weapons into farming tools and took a more peaceful path forward — although I have a couple of cousins…never mind.

It's been fun to find from whence my family came. But after having a three-day dalliance with days-of-old, two things jump out at me. The first is that we are all foreigners — every one of us. A few centuries here, and few centuries there, but humanity is constantly on the move — and often bloodshed follows. Perhaps we’ve learned our lesson over time and welcoming the stranger in the days ahead will be an art that we finally and peacefully perfect. Actually, I think Christians have a mandate to do so. See Romans 15:1-6.

The second thing is that we are who we are where we are. It’s been fun to romanticize about having Highland roots. We love being part of the local culture here in Scotland, and Judi will probably start making potato-leek soup when we get back to Colorado. (Her mother’s family is also Scotch-Irish.) But the truth is, I could wrap on a kilt and chase the deer on Sgùrr Alasdair all day long, but I’m not a Highlander any more than I’m a Viking voyager or an Irish cottier.

We all need to appreciate, even celebrate, our heritage. But if we regularly tie our identity to the hitching post of heredity, rather than the rail of current reality, we could forget where we truly live and what’s expected of us. Overemphasizing that someone is an Italian American, Mexican American (Chicano), African American, Asian American, or however it's declared in these days of political correctness, results in more isolation and less assimilation.

I encourage you to explore your heritage, whatever it might be, but be who you are where you are. And if in your searching you find out that we might be distant relatives, let me know.

Notwithstanding, in our past visits to Scotland, we’ve never been able to find anything bearing the colors of my mother’s father’s family. They were Scotch-Irish with the surname Gillogly. On those occasions when we inquired about our kin’s woven standard, the shop clerks would always get puzzled looks on their faces and say they were unfamiliar with the name — and then refer us to another shop that had more inventory or a self-avowed genealogy expert.

Actually, we didn’t need the latter. My mother’s sister was a genealogy aficionado. Long before the days of the Internet and ancestory.com, she taught college-level courses on lineage research. By spending countless hours in libraries, courthouses, and cemeteries, she traced her father’s ancestors back to Europe in the 17th century. Thanks to her diligence, we knew when, why, and how our people journeyed from Ireland to the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia to the mountains of western Pennsylvania to the hills of southeastern Ohio. In the “old country,” they were farmers who worked the land on several islands in Lower Lough Erne, near Enniskillen, in County Fermanagh, Ulster. My fifth great-grandparents, John and Mary Jane (Moore) Gillogly were both born in Enniskillen in 1847 but died in Muskingum County Ohio, she in 1816 and he in 1855 — yes, he lived to be 108.

But what about the Scottish origin, and what took them to Ireland? Starting in the early 1600s, Scottish protestants living largely in Dunfries and The Borders, the southernmost parts of the country, were coerced, even forced, to leave their homes and move west across the water to populate the Plantation of Ulster so England would have a foothold in Ireland. Those peasant pawns were the first to be known as Scotch-Irish. The English plan was to confiscate all the lands of Gaelic Irish nobility and set the Scots up as farmers on those same properties. But the farmers weren’t fighters. For this plan to work, they needed enforcers. So London looked north and decided the rascally, rugged Highlanders who had been giving them fits since the days of William Wallace were who they needed to hire.

But what’s interesting is that many Highland warriors were already in Ireland — recruited hundreds of years earlier to comprise private armies for Irish chieftains. The irony is that by the 1600s, you had Highlanders protecting the Irish from Highlanders serving as soldiers for the English. Whenever my relatives got to Ireland — probably in the 1200s or 1300s — and whatever side they were on — probably the Irish — they were apparently mercenaries. As a neighbor here in Plockton told me, “Highlanders don’t need much of a reason to fight.”

But why no personalized plaid? What I recently learned was that Gillogly was an Anglicized forms of the Irish surname Galloglaigh, which was an Irish variant of the Gaelic name MacGalloglach. In Gaelic, the mac, of course, means “son of.” The gall part means “foreigner” and oglach (or owglass) means young warrior. Pushing this historical door open a bit further, it seems my Scottish ancestors were heavily armed fighters referred to as Gaelic-Norse who originally rowed over from the Skrettingland area of southeast Norway. Essentially, they were Viking marauders and plunderers who liked what they saw in Scotland and decided not to row back. But instead of being known by their family, they were known by their macabre profession, and thus there was no family crest or tartan. However, the Scottish home base for the MacGalloglach clan was the Balmartin area of North Uist in the Outer Hebrides, Scotland’s far northwestern islands. That means they would have been intermingled and probably intermarried with the Clan MacDonald who laid hold to that land early on. Now that I know, I guess the closest I’ll ever get to a Gillogly tartan, is a MacDonald hand-me-down.

In Act 1, Scene 2 of Shakespeare’s Macbeth, an unnamed wounded soldier tells King Duncan and his sons, “…the merciless Macdonwald....from the Western Isles of kerns and gallowglasses is supplied.” In other words, the MacDonalds had military might at their disposal: the Kerns, lightly armed foot soldiers who generally carried a wooden shield and a sword; and the Gallowglass (a.k.a., Galloglachs… Galloglaighs…Gilloglys), heavily armored warriors hand-picked for their strength and massive size. They were known for carrying halberds, which were battle axes on long poles. Thankfully, they eventually beat their weapons into farming tools and took a more peaceful path forward — although I have a couple of cousins…never mind.

It's been fun to find from whence my family came. But after having a three-day dalliance with days-of-old, two things jump out at me. The first is that we are all foreigners — every one of us. A few centuries here, and few centuries there, but humanity is constantly on the move — and often bloodshed follows. Perhaps we’ve learned our lesson over time and welcoming the stranger in the days ahead will be an art that we finally and peacefully perfect. Actually, I think Christians have a mandate to do so. See Romans 15:1-6.

The second thing is that we are who we are where we are. It’s been fun to romanticize about having Highland roots. We love being part of the local culture here in Scotland, and Judi will probably start making potato-leek soup when we get back to Colorado. (Her mother’s family is also Scotch-Irish.) But the truth is, I could wrap on a kilt and chase the deer on Sgùrr Alasdair all day long, but I’m not a Highlander any more than I’m a Viking voyager or an Irish cottier.

We all need to appreciate, even celebrate, our heritage. But if we regularly tie our identity to the hitching post of heredity, rather than the rail of current reality, we could forget where we truly live and what’s expected of us. Overemphasizing that someone is an Italian American, Mexican American (Chicano), African American, Asian American, or however it's declared in these days of political correctness, results in more isolation and less assimilation.

I encourage you to explore your heritage, whatever it might be, but be who you are where you are. And if in your searching you find out that we might be distant relatives, let me know.

There's More Where That Came From

03/02/24 11:10

We’re completely content with the simplicity that abounds in our humble hamlet of Plockton. Take, for example, the procurement of groceries. The biggest store in the Highlands is Morrisons in Inverness, two hours and ten minutes northeast by train. There are smaller food co-ops in Kyle of Lochalsh, Broadford, and Portree. But here in our village, the main market is Plockton Shores.

This unassuming shop blends in with the long row of look-alike homes on Harbour Street — all of which were built to house herring fishermen and their families in a former century. Karen (pronounced Kay´-ruen) is Plockton Shores’ primary operative. Her always-bright welcome is a suitable substitute for sunshine on back-to-back days of Scottish mist and opaque skies.

The north side of the establishment is a café that serves homecooked meals and local brews. It’s open for breakfast and lunch this time of year — and dinner when warmer weather and a longer-lingering sun on the craigs lures tourists to town for fabulous photo ops and a loch-side supper.

The south half of the store is where locals buy stamps for the post — the red box is just two doors down — The Daily Record, fresh baked goods, and takeaway tea and coffee. But more than that, the south side’s also the village grocery.

Five steps further inside there’s a fresh produce section where 15 different fruits and vegetables share space in ten wicker bins on the wall. Naturally, you’ll find a neep or two (think rutabaga). You can’t serve haggis without mashed neeps. But the potatoes and leeks are the first to sell out every week as they are the named players in potato-leek soup, a Scottish favorite. (Judi has tried out two recipes so far. One was good enough to give a portion to the pastor to take home when he stopped by for a visit two evenings back.)

On adjacent shelving there are tins (cans) of Cullen Skink, Cock-a Leekie (also made with leeks), and a couple of other soups. You’ll find a few tubes of biscuits (crackers) and some bags of crisps (chips). The bread table has about a dozen loaves when freshly stocked, plus there’s a few sacks of flour underneath for those who’d rather bake their own.

Behind the till is a glass-fronted fridge with a sampling of butter, yogurt, and cheese, plus a pack or two of pork sausage. Squash (diluted juice) and fizzy drinks are kept cold on the bottom shelves. You can always find Coke, craved the world over, and Irn-Bru, a unique soda with popularity that starts to go flat south of Glasgow.

Beer and various household necessities occupy the rest of the shelves in Plockton Shores. If it’s not in stock, you can borrow from a neighbor until the next trip to Kyle.

What’s amazing is that the entire market takes up about 90 square feet!

Before I go on, I would be remiss not to mention auxiliary sustenance sales in our little village. Many of the crofts vend fresh eggs and preserves. You just have to know what lane to walk down, which barn door to enter, and where to leave your pounds. But our favorite food buying experience rolls our way every Wednesday: Yogi’s seafood van. In probably 20 cubic feet of refrigerated space in the back end of his wee lorry he portions out fillets of salmon, haddock, smoked haddock, halibut, hake, and monkfish, plus langoustines and other crustations. He simply blows his horn, and the locals scurry out to the street to see what fish have been freshly caught. Yogi is a grown-up version of the Good Humor man. Instead of a King Cone you get king crab.

I must admit, it's novel to live for a time in this world of reduced options and limited supply. It’s a world away from the mega stores in major cities — even Inverness — where the contents of just the endcap displays in the first two aisles would be more than Plockton Shores’ shelves could hold.

Buying food in our current location certainly makes us appreciate both the incredible variety and sheer volume of commodities that are found where we usually shop. It also reinforces the fact that the having vs. lacking match is always won in the late innings by the latter. We find ourselves paying more attention to our pantry than we do at home, and asking each other what needs to be used up next before it goes bad.

There’s absolutely no question about it: We can very easily adjust and live well on the inventory of local stores here in the Highlands. People all around us have done it for decades. We’re actually quite content. And the generosity of friends is always an added blessing. Even so, the word that that I’m contemplating during this season is abundance. There is scarcity — which we are far from. Then there’s sufficiency — which is where we are. Abundance is what one finds in Inverness or Glasgow or Colorado Springs.

The question I’m pondering: When it comes to God’s spiritual inventory in his storehouse of blessing, am I content with sufficiency even though abundance is always available?

“[God] is able to do exceedingly abundantly above all that we ask or think, according to the power that works in us… (Ephesians 3:20, KJV).

“I have come that they may have life, and that they may have it more abundantly” (John 10:10, KJV).

How many times do we hurry to a corner store for spiritual staples when our Heavenly Father’s supermarket is open ‘round the clock? What’s more, His inventory is infinite. Even when we empty a shelf, there’s always more where that came from.

This unassuming shop blends in with the long row of look-alike homes on Harbour Street — all of which were built to house herring fishermen and their families in a former century. Karen (pronounced Kay´-ruen) is Plockton Shores’ primary operative. Her always-bright welcome is a suitable substitute for sunshine on back-to-back days of Scottish mist and opaque skies.

The north side of the establishment is a café that serves homecooked meals and local brews. It’s open for breakfast and lunch this time of year — and dinner when warmer weather and a longer-lingering sun on the craigs lures tourists to town for fabulous photo ops and a loch-side supper.

The south half of the store is where locals buy stamps for the post — the red box is just two doors down — The Daily Record, fresh baked goods, and takeaway tea and coffee. But more than that, the south side’s also the village grocery.

Five steps further inside there’s a fresh produce section where 15 different fruits and vegetables share space in ten wicker bins on the wall. Naturally, you’ll find a neep or two (think rutabaga). You can’t serve haggis without mashed neeps. But the potatoes and leeks are the first to sell out every week as they are the named players in potato-leek soup, a Scottish favorite. (Judi has tried out two recipes so far. One was good enough to give a portion to the pastor to take home when he stopped by for a visit two evenings back.)

On adjacent shelving there are tins (cans) of Cullen Skink, Cock-a Leekie (also made with leeks), and a couple of other soups. You’ll find a few tubes of biscuits (crackers) and some bags of crisps (chips). The bread table has about a dozen loaves when freshly stocked, plus there’s a few sacks of flour underneath for those who’d rather bake their own.

Behind the till is a glass-fronted fridge with a sampling of butter, yogurt, and cheese, plus a pack or two of pork sausage. Squash (diluted juice) and fizzy drinks are kept cold on the bottom shelves. You can always find Coke, craved the world over, and Irn-Bru, a unique soda with popularity that starts to go flat south of Glasgow.

Beer and various household necessities occupy the rest of the shelves in Plockton Shores. If it’s not in stock, you can borrow from a neighbor until the next trip to Kyle.

What’s amazing is that the entire market takes up about 90 square feet!

Before I go on, I would be remiss not to mention auxiliary sustenance sales in our little village. Many of the crofts vend fresh eggs and preserves. You just have to know what lane to walk down, which barn door to enter, and where to leave your pounds. But our favorite food buying experience rolls our way every Wednesday: Yogi’s seafood van. In probably 20 cubic feet of refrigerated space in the back end of his wee lorry he portions out fillets of salmon, haddock, smoked haddock, halibut, hake, and monkfish, plus langoustines and other crustations. He simply blows his horn, and the locals scurry out to the street to see what fish have been freshly caught. Yogi is a grown-up version of the Good Humor man. Instead of a King Cone you get king crab.

I must admit, it's novel to live for a time in this world of reduced options and limited supply. It’s a world away from the mega stores in major cities — even Inverness — where the contents of just the endcap displays in the first two aisles would be more than Plockton Shores’ shelves could hold.

Buying food in our current location certainly makes us appreciate both the incredible variety and sheer volume of commodities that are found where we usually shop. It also reinforces the fact that the having vs. lacking match is always won in the late innings by the latter. We find ourselves paying more attention to our pantry than we do at home, and asking each other what needs to be used up next before it goes bad.

There’s absolutely no question about it: We can very easily adjust and live well on the inventory of local stores here in the Highlands. People all around us have done it for decades. We’re actually quite content. And the generosity of friends is always an added blessing. Even so, the word that that I’m contemplating during this season is abundance. There is scarcity — which we are far from. Then there’s sufficiency — which is where we are. Abundance is what one finds in Inverness or Glasgow or Colorado Springs.

The question I’m pondering: When it comes to God’s spiritual inventory in his storehouse of blessing, am I content with sufficiency even though abundance is always available?

“[God] is able to do exceedingly abundantly above all that we ask or think, according to the power that works in us… (Ephesians 3:20, KJV).

“I have come that they may have life, and that they may have it more abundantly” (John 10:10, KJV).

How many times do we hurry to a corner store for spiritual staples when our Heavenly Father’s supermarket is open ‘round the clock? What’s more, His inventory is infinite. Even when we empty a shelf, there’s always more where that came from.