The Power of Place

10/03/24 21:01

My grandfather never seemed to mind that the twentieth century was passing him by. He just didn’t care for conveniences. Though he did own a Model-T Ford, it was permanently parked in one of his barns, encased in decades of dust. Dewey Gillogly walked everywhere he went.

Until the day he died, Dewey drew his water from an ancient spring at the base of the hill that held his house. Some of my kinfolk back in those southeastern Ohio hollows swear it was the untreated water that killed him, but since he lived to be 92, their arguments are a lot shallower than that old spring must have been. Every morning, with pail in hand, he would bound off his back porch and head down the well-worn path to pull up enough drinking and washing water to get him through another day.

It was probably the area’s first permanent settlers who deepened the spring’s basin and lined it with slate. At some point a tin roof was purportedly raised overtop to protect the pool from falling leaves and debris. By the time Dewey came along there was standing a 10’ x 15’ cement-floored springhouse. The overhanging pitched roof covered the actual spring. Behind the wide wooden door, the water flowed through a trough in the floor, along the north wall. It was a place where melons and steel cans of raw milk were kept cool. The elevated portion of the floor was where my grandfather stored the sacks of potatoes he harvested from his fields up behind the house, or the apples he picked from the orchard in the side yard. The air inside had a dank, earthy smell, but with a strange scent of sweetness.

During my childhood, all my Ohio aunts and uncles lived in the rural regions surrounding the Gillogly homestead. Some were close enough that they could hear the report of Dewey’s shotgun echoing through the hills. I, on the other hand, was a distant relative in the literal sense of the term, growing up in ever-progressive New Jersey. But once or twice a year, my parents would head west in our Hudson Hornet for a Buckeye visit, and I would reconnect with my cousins. We’d scamper through the cornfields, get dirty in the coal shed, get wet in the creek, catch snakes in the stone foundation of the smokehouse, and look for treasures along the rails of the New York Central spur line that ran through the woods, just west of the house.

But on those warm August afternoons, when my parents and I had Grandpa and the farm to ourselves, I would eventually wander away from the grown-up discourse and find my way to the springhouse. There, I would lie on the bank and stare up into the bright green canopy of the sycamore trees that towered overhead. I’d study the twisted branches and watch squirrels leap from limb to limb. I would close my eyes and try to distinguish the calls of the cardinals from those of the robins. With my eyes still closed I would ponder life (as deeply as a nine-year old can ever ponder anything). When my imagination awoke, I would pretend that the springhouse was a garrison and I was the commander of its loyal troop, fighting off make-believe foes with sticks and stones.

When we’d visit in autumn, the sycamores would lay a golden carpet all around the springhouse. I was particularly drawn to the place at that time of year. As I got older, I would sit on the slate-topped stone wall that formed the front of the springhouse, with my back against a corner post, and read for hours on end, fully absorbed in the quiet coolness of that special setting. Looking back on my later-teen years, I’d have to say that some of my very important long-term plans were prayerfully developed in the shadows of that old shack.

That springhouse will always be a sacred place to me. For an adolescent, it was a safe haven — a place where life took a shady side road, skirting arduous arithmetic assignments, playground bullies, and the increasing business in the burgeoning Levittowns that were epitomizing East Coast life as I knew it. For a young man, walking down to that springhouse was like going to visit a trusted friend — one who provided a link to my past, but moreover, cared about my future.

Every few years, I’d get a chance to return to my Ohio roots . . . and witness how time has whittled away at the old homestead. Today, the wide swath of grass that used to be a main road ends in a thicket just beyond where the house used to stand. The rails, ties, and ballast that formed the spur line are long gone. Two of my cousins have divided up the property. The coal shed has disappeared. So have the smokehouse and the other outbuildings. Grass is the only thing that now grows on the hillsides that were once furrowed fields. But the springhouse remains. A stubborn survivor of change, it yet sits at the foot of the hill like a proud monument to the power of place. But even if it were gone, it would still be there in my mind, and I would occasionally visit it and relive the moments that I savored in its shelter.

All of us have a need for such private places in our lives — places of peace where we can go for a reprieve from routines and explore our innermost feelings — natural settings of sanctity where we can, as Christ followers, ponder the promises of Scripture and seek the heart of God.

Jesus, Himself, retreated to such private places on a reoccurring basis — probably more often than we’re even told in Scripture. After all, it was His Father who pointed out, as far back as Genesis, that rest and reflection needed to follow a marked time of toil. Whether it was to clear his mind or to get clear direction, Jesus would disengage from the demanding crowds or His conventional confines and escape to a quiet place in the open air — a garden, a mountainside, the seashore, the wilderness.

That’s exactly what Judi and I found during our multi-month Scotland escape. The indigo loch reflecting the firmament, the castle terrets beneath the rocky craigs, the sound of circling seagulls, the Kyle-bound train passing by on the opposite shore, the distinct smell of coal smoke from a dozen different chimneys: This was our backdrop for treasured memories that will increase in value as the years roll by. The power of place enriched our deep conversations on long hikes and short walks.

Where is your private place where you can temporarily let the rest of the world roll by? A Highlands village worked perfectly for us, but you don’t have to go to a distant land. Your special place can be the porch of a cabin nestled in the pines beside a placid lake, a long wooden dock on a wide lake, or even a small gazebo in a backyard garden where the noise of the neighborhood can be temporarily turned down. If you don’t have such places in your life, I strongly encourage you to find one and retreat to it as often as you can. We all need regular respites from the rush. We need a quiet place where we can make memories and engage in meaningful meditation to soothe our soul.

Until the day he died, Dewey drew his water from an ancient spring at the base of the hill that held his house. Some of my kinfolk back in those southeastern Ohio hollows swear it was the untreated water that killed him, but since he lived to be 92, their arguments are a lot shallower than that old spring must have been. Every morning, with pail in hand, he would bound off his back porch and head down the well-worn path to pull up enough drinking and washing water to get him through another day.

It was probably the area’s first permanent settlers who deepened the spring’s basin and lined it with slate. At some point a tin roof was purportedly raised overtop to protect the pool from falling leaves and debris. By the time Dewey came along there was standing a 10’ x 15’ cement-floored springhouse. The overhanging pitched roof covered the actual spring. Behind the wide wooden door, the water flowed through a trough in the floor, along the north wall. It was a place where melons and steel cans of raw milk were kept cool. The elevated portion of the floor was where my grandfather stored the sacks of potatoes he harvested from his fields up behind the house, or the apples he picked from the orchard in the side yard. The air inside had a dank, earthy smell, but with a strange scent of sweetness.

During my childhood, all my Ohio aunts and uncles lived in the rural regions surrounding the Gillogly homestead. Some were close enough that they could hear the report of Dewey’s shotgun echoing through the hills. I, on the other hand, was a distant relative in the literal sense of the term, growing up in ever-progressive New Jersey. But once or twice a year, my parents would head west in our Hudson Hornet for a Buckeye visit, and I would reconnect with my cousins. We’d scamper through the cornfields, get dirty in the coal shed, get wet in the creek, catch snakes in the stone foundation of the smokehouse, and look for treasures along the rails of the New York Central spur line that ran through the woods, just west of the house.

But on those warm August afternoons, when my parents and I had Grandpa and the farm to ourselves, I would eventually wander away from the grown-up discourse and find my way to the springhouse. There, I would lie on the bank and stare up into the bright green canopy of the sycamore trees that towered overhead. I’d study the twisted branches and watch squirrels leap from limb to limb. I would close my eyes and try to distinguish the calls of the cardinals from those of the robins. With my eyes still closed I would ponder life (as deeply as a nine-year old can ever ponder anything). When my imagination awoke, I would pretend that the springhouse was a garrison and I was the commander of its loyal troop, fighting off make-believe foes with sticks and stones.

When we’d visit in autumn, the sycamores would lay a golden carpet all around the springhouse. I was particularly drawn to the place at that time of year. As I got older, I would sit on the slate-topped stone wall that formed the front of the springhouse, with my back against a corner post, and read for hours on end, fully absorbed in the quiet coolness of that special setting. Looking back on my later-teen years, I’d have to say that some of my very important long-term plans were prayerfully developed in the shadows of that old shack.

That springhouse will always be a sacred place to me. For an adolescent, it was a safe haven — a place where life took a shady side road, skirting arduous arithmetic assignments, playground bullies, and the increasing business in the burgeoning Levittowns that were epitomizing East Coast life as I knew it. For a young man, walking down to that springhouse was like going to visit a trusted friend — one who provided a link to my past, but moreover, cared about my future.

Every few years, I’d get a chance to return to my Ohio roots . . . and witness how time has whittled away at the old homestead. Today, the wide swath of grass that used to be a main road ends in a thicket just beyond where the house used to stand. The rails, ties, and ballast that formed the spur line are long gone. Two of my cousins have divided up the property. The coal shed has disappeared. So have the smokehouse and the other outbuildings. Grass is the only thing that now grows on the hillsides that were once furrowed fields. But the springhouse remains. A stubborn survivor of change, it yet sits at the foot of the hill like a proud monument to the power of place. But even if it were gone, it would still be there in my mind, and I would occasionally visit it and relive the moments that I savored in its shelter.

All of us have a need for such private places in our lives — places of peace where we can go for a reprieve from routines and explore our innermost feelings — natural settings of sanctity where we can, as Christ followers, ponder the promises of Scripture and seek the heart of God.

Jesus, Himself, retreated to such private places on a reoccurring basis — probably more often than we’re even told in Scripture. After all, it was His Father who pointed out, as far back as Genesis, that rest and reflection needed to follow a marked time of toil. Whether it was to clear his mind or to get clear direction, Jesus would disengage from the demanding crowds or His conventional confines and escape to a quiet place in the open air — a garden, a mountainside, the seashore, the wilderness.

That’s exactly what Judi and I found during our multi-month Scotland escape. The indigo loch reflecting the firmament, the castle terrets beneath the rocky craigs, the sound of circling seagulls, the Kyle-bound train passing by on the opposite shore, the distinct smell of coal smoke from a dozen different chimneys: This was our backdrop for treasured memories that will increase in value as the years roll by. The power of place enriched our deep conversations on long hikes and short walks.

Where is your private place where you can temporarily let the rest of the world roll by? A Highlands village worked perfectly for us, but you don’t have to go to a distant land. Your special place can be the porch of a cabin nestled in the pines beside a placid lake, a long wooden dock on a wide lake, or even a small gazebo in a backyard garden where the noise of the neighborhood can be temporarily turned down. If you don’t have such places in your life, I strongly encourage you to find one and retreat to it as often as you can. We all need regular respites from the rush. We need a quiet place where we can make memories and engage in meaningful meditation to soothe our soul.

Are You Hearing Me?

01/03/24 12:44

THE WORDS

Even before we moved into our Scottish cottage, Judi and I were somewhat familiar with the language nuances between the U.S. and the U.K. Here are some of the common Scottish words and terms to which we’ve been reintroduced:

· In Scotland, potatos are tatties, French fries are chips, and our chips are their crisps. And if you eat too many of any of those, it’s not your pants that you’ll have trouble snapping, it’s your trousers.

· Over here, a jumper is a pullover garment, not someone about to bound off a ten-story ledge; and trainers are not the fit folks at the gym pushing you to do one more pull-up, rather, it’s what you wear on your feet when you’re there working out.

· You might think you would go to the supermarket with your shopping list and push a cart. But actually, you go to the grocery with your messages and wheel a trolley — that is, if you have a pound in your pocket to buy its temporary freedom from the others it’s chained to. And if you have a wee bairn at home, you’ll probably want to toss some nappies in that trolley. And maybe you’ll want a tin of shortbread biscuits and some squash to mix up and wash them down.

· You don’t keep a flashlight in the trunk so you can see what you’re doing at night when you pull onto the shoulder to change a tire. Rather, you keep a torch in your boot so that when you finally get to a passing place you can…try to read the microscopic instruction on the mini tyre compressor you’re glaring at since none of the cars in Scotland these days carry spares. (Good luck if you have a blowout after dark on an unlit single track in the mountains where there are no lay-bys. But I’ll save expounding on that for another blog.)

· There are plenty more. A toastie is not how you feel sitting in front of the coal stove, it’s a grilled sandwich. Being invited for a cuppa means you’re going to drink tea. If you have legal problems, you don’t look for a lawyer but a solicitor — unless you need somebody to defend you, and then you need a barrister. A burn won’t catch on fire because it’s a small stream. A moor is a swamp where numerous burns and the endless Scottish rain pool together. (There are more moors than you imagine.) A lass is a young man. A lassie is a young woman, and when several lassies get together to celebrate one’s upcoming betrothal, it’s a hen party. Bonnie means pretty. You can also say braw or tidy, which is the opposite of hackit. A coo is a shaggy cow, and shag has nothing to do with carpet. I’m sure you ken what I mean.

Even though we’re usually connecting all the dots, we still get caught off guard. Like last week:

Places to fill up the car with fuel are few and far between in the Highlands. If we’re traveling north, the closest station to the cottage is 19 miles, up and around the head of the loch in the village of Lochcarron. After that, it’s 29 miles to the next one in Kinlochewe, and another 32 to the one after that.

Last week, I pulled into Lochcarron station and noticed what looked like plastic flags on the handles of the green pumps. (In Scotland, opposite of what American drivers are used to, green-handles signify unleaded while black indicate diesel. Don’t get them confused!)

Thinking the streamers were tags indicating they were out, I walked in and asked Charlotte, “Do you not have gas today?”

“I’m afraid not,” she replied, “We’ll get some bottles in next week.” Her response slipped right by me because I was straightaway trying to decide if I wanted to chance going 29 or more miles north, or double back south 27 miles, past our cottage, just to fill up.

“But if you’re talking about the pumps,” Charlotte interrupted with a knowing look, “we have plenty of diesel and petrol.” Oh yeah. Petrol! That’s the word. It turns out that what I thought were flags were mini rolls of plastic gloves that pumpers can wear to minimize getting petroleum residue on the hands.

Yes, we’re still learning the lingo.

THE SIGNAGE

We’ve mastered driving on the left with the steering wheel on the right, but it’s the signage we constantly encounter — even on trails and in establishments — that have us questioning and chuckling and sometimes going back for a second look. Here are a few of our favorites that we’ve managed to snap as we’ve been out and about. We’ll let you draw your own conclusions.

THE ACCENT

This brings me to the trickiest part of communication in Scotland, the brogue. Let me say up front that I absolutely love the Scottish pronunciations and I adore the way certain phrases roll smoothly off the tongue like the fog rolling over the heather on the braes at morning’s first light. I also realize that, over here, we are the people with the accents. But honestly, sometimes trying to understand is like trying to figure out a word riddle, particularly when we encounter someone from Glasgow or a remote isle. Following a conversation with such a person, Judi and I will quickly and quietly step to the side and ask each other, “How much of that did you get?” It’s not uncommon to discover that we each heard something entirely different.

Interestingly, those from over the southern border also have a hard time communicating with some of the Scots. There’s a story about a Scotsman walking through a field. He sees a man drinking water from a pool with his hand. The Scotsman shouts “Awa ye feel hoor that’s full O’ coos Sharn.” (Rough translation: Don't drink the water, it's full of cow…pies.) The man yells, “I’m an Englishman. Speak English. I don't understand you.” The Scotsman shouts back, “I said, use both hands; you'll get more in.”

The point to all of this is that good communication is a two-way venture. The speaker and the hearer must be on the same wavelength. Eye contact is critical because facial expressions give valuable insights to what’s really being said. And clear communication takes time. Judi and I have agreed that our extended time together — without her heading off to a tennis match or me rushing to the airport for another five-day business trip — has forced us to verbally process what each other is saying on a deeper level than we have experienced for many years.

You don’t have to come to Scotland to improve your communication, but if you do, you’re guaranteed a dialectal and cultural bounty to boot. As the Scots say, it will be pure dead brilliant.

Even before we moved into our Scottish cottage, Judi and I were somewhat familiar with the language nuances between the U.S. and the U.K. Here are some of the common Scottish words and terms to which we’ve been reintroduced:

· In Scotland, potatos are tatties, French fries are chips, and our chips are their crisps. And if you eat too many of any of those, it’s not your pants that you’ll have trouble snapping, it’s your trousers.

· Over here, a jumper is a pullover garment, not someone about to bound off a ten-story ledge; and trainers are not the fit folks at the gym pushing you to do one more pull-up, rather, it’s what you wear on your feet when you’re there working out.

· You might think you would go to the supermarket with your shopping list and push a cart. But actually, you go to the grocery with your messages and wheel a trolley — that is, if you have a pound in your pocket to buy its temporary freedom from the others it’s chained to. And if you have a wee bairn at home, you’ll probably want to toss some nappies in that trolley. And maybe you’ll want a tin of shortbread biscuits and some squash to mix up and wash them down.

· You don’t keep a flashlight in the trunk so you can see what you’re doing at night when you pull onto the shoulder to change a tire. Rather, you keep a torch in your boot so that when you finally get to a passing place you can…try to read the microscopic instruction on the mini tyre compressor you’re glaring at since none of the cars in Scotland these days carry spares. (Good luck if you have a blowout after dark on an unlit single track in the mountains where there are no lay-bys. But I’ll save expounding on that for another blog.)

· There are plenty more. A toastie is not how you feel sitting in front of the coal stove, it’s a grilled sandwich. Being invited for a cuppa means you’re going to drink tea. If you have legal problems, you don’t look for a lawyer but a solicitor — unless you need somebody to defend you, and then you need a barrister. A burn won’t catch on fire because it’s a small stream. A moor is a swamp where numerous burns and the endless Scottish rain pool together. (There are more moors than you imagine.) A lass is a young man. A lassie is a young woman, and when several lassies get together to celebrate one’s upcoming betrothal, it’s a hen party. Bonnie means pretty. You can also say braw or tidy, which is the opposite of hackit. A coo is a shaggy cow, and shag has nothing to do with carpet. I’m sure you ken what I mean.

Even though we’re usually connecting all the dots, we still get caught off guard. Like last week:

Places to fill up the car with fuel are few and far between in the Highlands. If we’re traveling north, the closest station to the cottage is 19 miles, up and around the head of the loch in the village of Lochcarron. After that, it’s 29 miles to the next one in Kinlochewe, and another 32 to the one after that.

Last week, I pulled into Lochcarron station and noticed what looked like plastic flags on the handles of the green pumps. (In Scotland, opposite of what American drivers are used to, green-handles signify unleaded while black indicate diesel. Don’t get them confused!)

Thinking the streamers were tags indicating they were out, I walked in and asked Charlotte, “Do you not have gas today?”

“I’m afraid not,” she replied, “We’ll get some bottles in next week.” Her response slipped right by me because I was straightaway trying to decide if I wanted to chance going 29 or more miles north, or double back south 27 miles, past our cottage, just to fill up.

“But if you’re talking about the pumps,” Charlotte interrupted with a knowing look, “we have plenty of diesel and petrol.” Oh yeah. Petrol! That’s the word. It turns out that what I thought were flags were mini rolls of plastic gloves that pumpers can wear to minimize getting petroleum residue on the hands.

Yes, we’re still learning the lingo.

THE SIGNAGE

We’ve mastered driving on the left with the steering wheel on the right, but it’s the signage we constantly encounter — even on trails and in establishments — that have us questioning and chuckling and sometimes going back for a second look. Here are a few of our favorites that we’ve managed to snap as we’ve been out and about. We’ll let you draw your own conclusions.

THE ACCENT

This brings me to the trickiest part of communication in Scotland, the brogue. Let me say up front that I absolutely love the Scottish pronunciations and I adore the way certain phrases roll smoothly off the tongue like the fog rolling over the heather on the braes at morning’s first light. I also realize that, over here, we are the people with the accents. But honestly, sometimes trying to understand is like trying to figure out a word riddle, particularly when we encounter someone from Glasgow or a remote isle. Following a conversation with such a person, Judi and I will quickly and quietly step to the side and ask each other, “How much of that did you get?” It’s not uncommon to discover that we each heard something entirely different.

Interestingly, those from over the southern border also have a hard time communicating with some of the Scots. There’s a story about a Scotsman walking through a field. He sees a man drinking water from a pool with his hand. The Scotsman shouts “Awa ye feel hoor that’s full O’ coos Sharn.” (Rough translation: Don't drink the water, it's full of cow…pies.) The man yells, “I’m an Englishman. Speak English. I don't understand you.” The Scotsman shouts back, “I said, use both hands; you'll get more in.”

The point to all of this is that good communication is a two-way venture. The speaker and the hearer must be on the same wavelength. Eye contact is critical because facial expressions give valuable insights to what’s really being said. And clear communication takes time. Judi and I have agreed that our extended time together — without her heading off to a tennis match or me rushing to the airport for another five-day business trip — has forced us to verbally process what each other is saying on a deeper level than we have experienced for many years.

You don’t have to come to Scotland to improve your communication, but if you do, you’re guaranteed a dialectal and cultural bounty to boot. As the Scots say, it will be pure dead brilliant.

Creation's Proclamation

23/02/24 16:51

There’s an old joke about a burley backwoodsman who applied for a job as a lumberjack, claiming to be the fastest axman alive. When the boss asked the calloused codger where he might have gained the experience necessary to do such a job, he responded that he worked for years as the lead cutter in the Sahara Forest. The boss, taken aback, inquired, “Are you talking about the Sahara Desert?” The boastful logger replied, “Yeah. That’s what they call it now.”

That same lumberjack must have also worked on the Orkney Islands. This curious archipelago off the north coast of mainland Scotland is almost totally void of forestation. In fact, there is a landmark on Albert Street in the town of Kirkwall known as “The Big Tree.” It’s a sacred 200-year-old sycamore that’s kept erect by a metal rod through its hollow trunk — an attempt to preserve it for future generations.

But even without woodlands, somehow these 70 separate islands — only 20 inhabited — come together to offer a peculiar beauty that promises to send pensive viewers into a melancholy state. Chartreuse hills tumble into inky peat bogs then rise again and climb to the overcast horizon. Now and then, brilliant sunbeams break through the steely skies to shine on countless sheep, grazing wherever they please. Ancient stone fences cordon off long-abandoned cottages made of matching material. The population today lives in newer farm compounds — cottages, barns and outbuildings clustered together in a way that when viewed from a distance look like wee kingdoms on a Carcassonne gameboard.

In the Orkneys, a coastline of some kind is seldom out of sight: off to the east, a sheer 300-meter cliff with angry waves beating its base; out to the west, a white-sand beach with rows of imbedded black strata temporarily holding back the tide. These settings are replete with winged wildlife as the Orkneys are home to the United Kingdom’s largest colonies of seabirds, which, when they’re not nesting, continuously glide and squawk aloft. Yet the dominant sound is always the howling wind from the North Sea. And that’s why the locals say they are treeless: salt air and constant gales.

But behind this desolate façade lurks some of Europe’s greatest mysteries. Roughly a half century before the first blocks were set in place at the Pyramids of Giza, a thriving colony existed on the Orkneys. Perfectly preserved under sand until 1850, Skara Brea now provides a pristine example of what life was like on these low-lying islands 3,000 years before Christ. Who these people were, how they got to these isolated islands, and where they went still has archeologists guessing.

Then there’s the nearby Ring of Brodgar, the third largest stone circle in the British Isles. Thirty-six of the original 60 stone slabs still stand. How it ties into the Skara Brea's culture remains a subject of debate between Neolithic historians. Was it a rudimentary astrological observatory or perhaps a temple? (Some archeologists think the Ring of Brodgar may have been a shrine for sun worship while the neighboring Stones of Stenness was a place to pay homage to the moon.)

Dozens of stone circles, chambered tombs, and burial mounds are scattered throughout the islands. Other settlement sites also exist — some with rudimentary indoor toilets! More are undoubtedly waiting to be discovered.

Nick Card, professor at the University of the Highlands and the director of excavations on the Orkney Islands, has written, “London may be the cultural hub of Britain today, but 5,000 years ago, Orkney was the centre for innovation for the British Isles. Ideas spread from this place. The first grooved pottery, which is so distinctive of the era, was made here, for example, and the first henges – stone rings with ditches round them – were erected on Orkney. Then the ideas spread to the rest of the Neolithic Britain. This was the font for new thinking at the time.”

As Judi and I explored these places — essentially having them to ourselves — we talked about what life would have been like for these people whose primary focus was to hunt, fish, and farm in order to survive another day. Did they have any inkling that the world was round and that there was a myriad of more-hospitable places to live?

We also talked about what might have been their concept of the Creator and whether their rituals around the stone rings might have left room for the God of the Bible. To ponder this exposes the possibility of divine subjectivity and the complexity of holy grace. Did these people have a sufficiently appropriate faith-response to God’s revelation through creation and to that which He placed in their hearts? Instead of thinking as the Ring of Brodgar and the Stones of Stenness as evil places of pagan ritual, perhaps they were constructed in an attempt to respond — the only way the Skara Brea people knew how — to that which was intrinsic and to reach out to a God whose name they never heard uttered.

“For ever since the world was created, people have seen the earth and sky. Through everything God made, they can clearly see his invisible qualities — his eternal power and divine nature” (Romans 1:20, NLT). And when those “who have never heard of God’s law follow it more or less by instinct, they confirm its truth by their obedience. They show that God’s law is not something alien, imposed on us from without, but woven into the very fabric of our creation. There is something deep within them that echoes God’s yes and no, right and wrong. Their response to God’s yes and no will become public knowledge on the day God makes his final decision about every man and woman” (Romans 2:15-16, The Message).

It’s likely that Paul in Athens was talking about people like those from Skara Brea when he said, “… we should not think that the divine being is like gold or silver or stone—an image made by human design and skill. In the past God overlooked such ignorance, but now he commands all people everywhere to repent” (Acts 17:29-30, NIV).

If God’s grace and mercy is applied as I trust it might be, maybe in heaven we’ll not only be able to coax Noah to describe his feelings when the first raindrops fell or inquire of Peter what it was like to walk on water, but also ask someone from Skara Brea who first came up with the idea of indoor plumbing.

That same lumberjack must have also worked on the Orkney Islands. This curious archipelago off the north coast of mainland Scotland is almost totally void of forestation. In fact, there is a landmark on Albert Street in the town of Kirkwall known as “The Big Tree.” It’s a sacred 200-year-old sycamore that’s kept erect by a metal rod through its hollow trunk — an attempt to preserve it for future generations.

But even without woodlands, somehow these 70 separate islands — only 20 inhabited — come together to offer a peculiar beauty that promises to send pensive viewers into a melancholy state. Chartreuse hills tumble into inky peat bogs then rise again and climb to the overcast horizon. Now and then, brilliant sunbeams break through the steely skies to shine on countless sheep, grazing wherever they please. Ancient stone fences cordon off long-abandoned cottages made of matching material. The population today lives in newer farm compounds — cottages, barns and outbuildings clustered together in a way that when viewed from a distance look like wee kingdoms on a Carcassonne gameboard.

In the Orkneys, a coastline of some kind is seldom out of sight: off to the east, a sheer 300-meter cliff with angry waves beating its base; out to the west, a white-sand beach with rows of imbedded black strata temporarily holding back the tide. These settings are replete with winged wildlife as the Orkneys are home to the United Kingdom’s largest colonies of seabirds, which, when they’re not nesting, continuously glide and squawk aloft. Yet the dominant sound is always the howling wind from the North Sea. And that’s why the locals say they are treeless: salt air and constant gales.

But behind this desolate façade lurks some of Europe’s greatest mysteries. Roughly a half century before the first blocks were set in place at the Pyramids of Giza, a thriving colony existed on the Orkneys. Perfectly preserved under sand until 1850, Skara Brea now provides a pristine example of what life was like on these low-lying islands 3,000 years before Christ. Who these people were, how they got to these isolated islands, and where they went still has archeologists guessing.

Then there’s the nearby Ring of Brodgar, the third largest stone circle in the British Isles. Thirty-six of the original 60 stone slabs still stand. How it ties into the Skara Brea's culture remains a subject of debate between Neolithic historians. Was it a rudimentary astrological observatory or perhaps a temple? (Some archeologists think the Ring of Brodgar may have been a shrine for sun worship while the neighboring Stones of Stenness was a place to pay homage to the moon.)

Dozens of stone circles, chambered tombs, and burial mounds are scattered throughout the islands. Other settlement sites also exist — some with rudimentary indoor toilets! More are undoubtedly waiting to be discovered.

Nick Card, professor at the University of the Highlands and the director of excavations on the Orkney Islands, has written, “London may be the cultural hub of Britain today, but 5,000 years ago, Orkney was the centre for innovation for the British Isles. Ideas spread from this place. The first grooved pottery, which is so distinctive of the era, was made here, for example, and the first henges – stone rings with ditches round them – were erected on Orkney. Then the ideas spread to the rest of the Neolithic Britain. This was the font for new thinking at the time.”

As Judi and I explored these places — essentially having them to ourselves — we talked about what life would have been like for these people whose primary focus was to hunt, fish, and farm in order to survive another day. Did they have any inkling that the world was round and that there was a myriad of more-hospitable places to live?

We also talked about what might have been their concept of the Creator and whether their rituals around the stone rings might have left room for the God of the Bible. To ponder this exposes the possibility of divine subjectivity and the complexity of holy grace. Did these people have a sufficiently appropriate faith-response to God’s revelation through creation and to that which He placed in their hearts? Instead of thinking as the Ring of Brodgar and the Stones of Stenness as evil places of pagan ritual, perhaps they were constructed in an attempt to respond — the only way the Skara Brea people knew how — to that which was intrinsic and to reach out to a God whose name they never heard uttered.

“For ever since the world was created, people have seen the earth and sky. Through everything God made, they can clearly see his invisible qualities — his eternal power and divine nature” (Romans 1:20, NLT). And when those “who have never heard of God’s law follow it more or less by instinct, they confirm its truth by their obedience. They show that God’s law is not something alien, imposed on us from without, but woven into the very fabric of our creation. There is something deep within them that echoes God’s yes and no, right and wrong. Their response to God’s yes and no will become public knowledge on the day God makes his final decision about every man and woman” (Romans 2:15-16, The Message).

It’s likely that Paul in Athens was talking about people like those from Skara Brea when he said, “… we should not think that the divine being is like gold or silver or stone—an image made by human design and skill. In the past God overlooked such ignorance, but now he commands all people everywhere to repent” (Acts 17:29-30, NIV).

If God’s grace and mercy is applied as I trust it might be, maybe in heaven we’ll not only be able to coax Noah to describe his feelings when the first raindrops fell or inquire of Peter what it was like to walk on water, but also ask someone from Skara Brea who first came up with the idea of indoor plumbing.

Just Another Foreigner

12/02/24 13:34

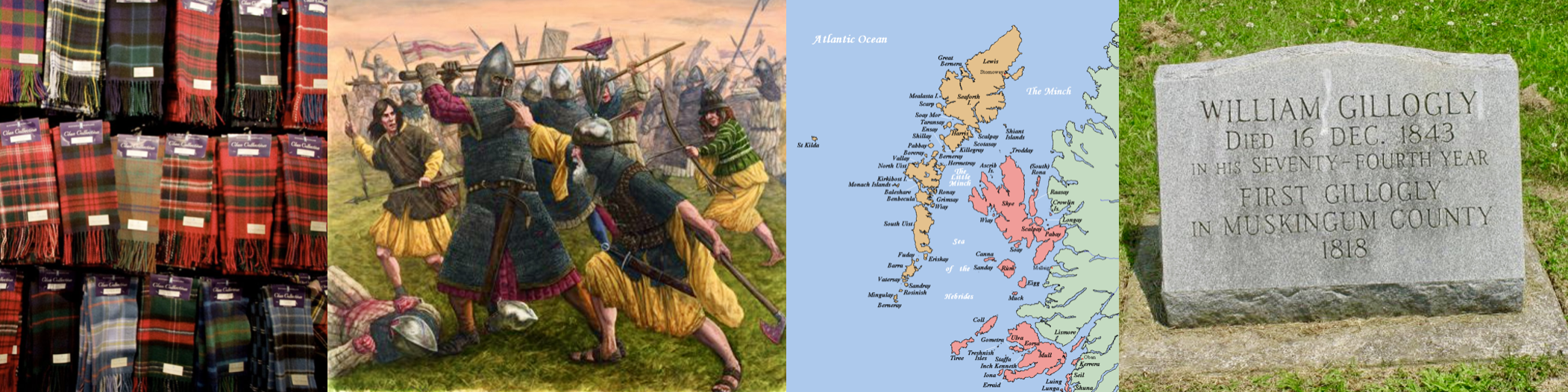

In any of the many tourist shops in Edinburgh, Glasgow, or Inverness, those of Scottish descent can purchase countless tartan products denoting their clan. If you’re a Stewart, Campbell, Fraser, MacDonald, MacLeod, MacKenzie, or any of the other 30 or more “Macs,” there’s a kilt, scarf, fly or tie in your personal plaid, either on the rack or in the back.

Notwithstanding, in our past visits to Scotland, we’ve never been able to find anything bearing the colors of my mother’s father’s family. They were Scotch-Irish with the surname Gillogly. On those occasions when we inquired about our kin’s woven standard, the shop clerks would always get puzzled looks on their faces and say they were unfamiliar with the name — and then refer us to another shop that had more inventory or a self-avowed genealogy expert.

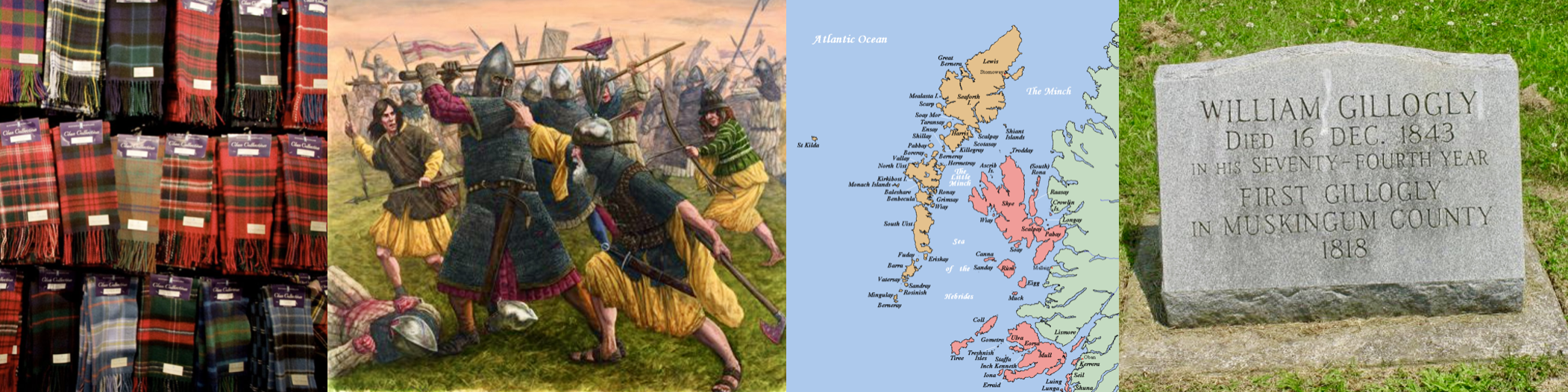

Actually, we didn’t need the latter. My mother’s sister was a genealogy aficionado. Long before the days of the Internet and ancestory.com, she taught college-level courses on lineage research. By spending countless hours in libraries, courthouses, and cemeteries, she traced her father’s ancestors back to Europe in the 17th century. Thanks to her diligence, we knew when, why, and how our people journeyed from Ireland to the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia to the mountains of western Pennsylvania to the hills of southeastern Ohio. In the “old country,” they were farmers who worked the land on several islands in Lower Lough Erne, near Enniskillen, in County Fermanagh, Ulster. My fifth great-grandparents, John and Mary Jane (Moore) Gillogly were both born in Enniskillen in 1847 but died in Muskingum County Ohio, she in 1816 and he in 1855 — yes, he lived to be 108.

But what about the Scottish origin, and what took them to Ireland? Starting in the early 1600s, Scottish protestants living largely in Dunfries and The Borders, the southernmost parts of the country, were coerced, even forced, to leave their homes and move west across the water to populate the Plantation of Ulster so England would have a foothold in Ireland. Those peasant pawns were the first to be known as Scotch-Irish. The English plan was to confiscate all the lands of Gaelic Irish nobility and set the Scots up as farmers on those same properties. But the farmers weren’t fighters. For this plan to work, they needed enforcers. So London looked north and decided the rascally, rugged Highlanders who had been giving them fits since the days of William Wallace were who they needed to hire.

But what’s interesting is that many Highland warriors were already in Ireland — recruited hundreds of years earlier to comprise private armies for Irish chieftains. The irony is that by the 1600s, you had Highlanders protecting the Irish from Highlanders serving as soldiers for the English. Whenever my relatives got to Ireland — probably in the 1200s or 1300s — and whatever side they were on — probably the Irish — they were apparently mercenaries. As a neighbor here in Plockton told me, “Highlanders don’t need much of a reason to fight.”

But why no personalized plaid? What I recently learned was that Gillogly was an Anglicized forms of the Irish surname Galloglaigh, which was an Irish variant of the Gaelic name MacGalloglach. In Gaelic, the mac, of course, means “son of.” The gall part means “foreigner” and oglach (or owglass) means young warrior. Pushing this historical door open a bit further, it seems my Scottish ancestors were heavily armed fighters referred to as Gaelic-Norse who originally rowed over from the Skrettingland area of southeast Norway. Essentially, they were Viking marauders and plunderers who liked what they saw in Scotland and decided not to row back. But instead of being known by their family, they were known by their macabre profession, and thus there was no family crest or tartan. However, the Scottish home base for the MacGalloglach clan was the Balmartin area of North Uist in the Outer Hebrides, Scotland’s far northwestern islands. That means they would have been intermingled and probably intermarried with the Clan MacDonald who laid hold to that land early on. Now that I know, I guess the closest I’ll ever get to a Gillogly tartan, is a MacDonald hand-me-down.

In Act 1, Scene 2 of Shakespeare’s Macbeth, an unnamed wounded soldier tells King Duncan and his sons, “…the merciless Macdonwald....from the Western Isles of kerns and gallowglasses is supplied.” In other words, the MacDonalds had military might at their disposal: the Kerns, lightly armed foot soldiers who generally carried a wooden shield and a sword; and the Gallowglass (a.k.a., Galloglachs… Galloglaighs…Gilloglys), heavily armored warriors hand-picked for their strength and massive size. They were known for carrying halberds, which were battle axes on long poles. Thankfully, they eventually beat their weapons into farming tools and took a more peaceful path forward — although I have a couple of cousins…never mind.

It's been fun to find from whence my family came. But after having a three-day dalliance with days-of-old, two things jump out at me. The first is that we are all foreigners — every one of us. A few centuries here, and few centuries there, but humanity is constantly on the move — and often bloodshed follows. Perhaps we’ve learned our lesson over time and welcoming the stranger in the days ahead will be an art that we finally and peacefully perfect. Actually, I think Christians have a mandate to do so. See Romans 15:1-6.

The second thing is that we are who we are where we are. It’s been fun to romanticize about having Highland roots. We love being part of the local culture here in Scotland, and Judi will probably start making potato-leek soup when we get back to Colorado. (Her mother’s family is also Scotch-Irish.) But the truth is, I could wrap on a kilt and chase the deer on Sgùrr Alasdair all day long, but I’m not a Highlander any more than I’m a Viking voyager or an Irish cottier.

We all need to appreciate, even celebrate, our heritage. But if we regularly tie our identity to the hitching post of heredity, rather than the rail of current reality, we could forget where we truly live and what’s expected of us. Overemphasizing that someone is an Italian American, Mexican American (Chicano), African American, Asian American, or however it's declared in these days of political correctness, results in more isolation and less assimilation.

I encourage you to explore your heritage, whatever it might be, but be who you are where you are. And if in your searching you find out that we might be distant relatives, let me know.

Notwithstanding, in our past visits to Scotland, we’ve never been able to find anything bearing the colors of my mother’s father’s family. They were Scotch-Irish with the surname Gillogly. On those occasions when we inquired about our kin’s woven standard, the shop clerks would always get puzzled looks on their faces and say they were unfamiliar with the name — and then refer us to another shop that had more inventory or a self-avowed genealogy expert.

Actually, we didn’t need the latter. My mother’s sister was a genealogy aficionado. Long before the days of the Internet and ancestory.com, she taught college-level courses on lineage research. By spending countless hours in libraries, courthouses, and cemeteries, she traced her father’s ancestors back to Europe in the 17th century. Thanks to her diligence, we knew when, why, and how our people journeyed from Ireland to the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia to the mountains of western Pennsylvania to the hills of southeastern Ohio. In the “old country,” they were farmers who worked the land on several islands in Lower Lough Erne, near Enniskillen, in County Fermanagh, Ulster. My fifth great-grandparents, John and Mary Jane (Moore) Gillogly were both born in Enniskillen in 1847 but died in Muskingum County Ohio, she in 1816 and he in 1855 — yes, he lived to be 108.

But what about the Scottish origin, and what took them to Ireland? Starting in the early 1600s, Scottish protestants living largely in Dunfries and The Borders, the southernmost parts of the country, were coerced, even forced, to leave their homes and move west across the water to populate the Plantation of Ulster so England would have a foothold in Ireland. Those peasant pawns were the first to be known as Scotch-Irish. The English plan was to confiscate all the lands of Gaelic Irish nobility and set the Scots up as farmers on those same properties. But the farmers weren’t fighters. For this plan to work, they needed enforcers. So London looked north and decided the rascally, rugged Highlanders who had been giving them fits since the days of William Wallace were who they needed to hire.

But what’s interesting is that many Highland warriors were already in Ireland — recruited hundreds of years earlier to comprise private armies for Irish chieftains. The irony is that by the 1600s, you had Highlanders protecting the Irish from Highlanders serving as soldiers for the English. Whenever my relatives got to Ireland — probably in the 1200s or 1300s — and whatever side they were on — probably the Irish — they were apparently mercenaries. As a neighbor here in Plockton told me, “Highlanders don’t need much of a reason to fight.”

But why no personalized plaid? What I recently learned was that Gillogly was an Anglicized forms of the Irish surname Galloglaigh, which was an Irish variant of the Gaelic name MacGalloglach. In Gaelic, the mac, of course, means “son of.” The gall part means “foreigner” and oglach (or owglass) means young warrior. Pushing this historical door open a bit further, it seems my Scottish ancestors were heavily armed fighters referred to as Gaelic-Norse who originally rowed over from the Skrettingland area of southeast Norway. Essentially, they were Viking marauders and plunderers who liked what they saw in Scotland and decided not to row back. But instead of being known by their family, they were known by their macabre profession, and thus there was no family crest or tartan. However, the Scottish home base for the MacGalloglach clan was the Balmartin area of North Uist in the Outer Hebrides, Scotland’s far northwestern islands. That means they would have been intermingled and probably intermarried with the Clan MacDonald who laid hold to that land early on. Now that I know, I guess the closest I’ll ever get to a Gillogly tartan, is a MacDonald hand-me-down.

In Act 1, Scene 2 of Shakespeare’s Macbeth, an unnamed wounded soldier tells King Duncan and his sons, “…the merciless Macdonwald....from the Western Isles of kerns and gallowglasses is supplied.” In other words, the MacDonalds had military might at their disposal: the Kerns, lightly armed foot soldiers who generally carried a wooden shield and a sword; and the Gallowglass (a.k.a., Galloglachs… Galloglaighs…Gilloglys), heavily armored warriors hand-picked for their strength and massive size. They were known for carrying halberds, which were battle axes on long poles. Thankfully, they eventually beat their weapons into farming tools and took a more peaceful path forward — although I have a couple of cousins…never mind.

It's been fun to find from whence my family came. But after having a three-day dalliance with days-of-old, two things jump out at me. The first is that we are all foreigners — every one of us. A few centuries here, and few centuries there, but humanity is constantly on the move — and often bloodshed follows. Perhaps we’ve learned our lesson over time and welcoming the stranger in the days ahead will be an art that we finally and peacefully perfect. Actually, I think Christians have a mandate to do so. See Romans 15:1-6.

The second thing is that we are who we are where we are. It’s been fun to romanticize about having Highland roots. We love being part of the local culture here in Scotland, and Judi will probably start making potato-leek soup when we get back to Colorado. (Her mother’s family is also Scotch-Irish.) But the truth is, I could wrap on a kilt and chase the deer on Sgùrr Alasdair all day long, but I’m not a Highlander any more than I’m a Viking voyager or an Irish cottier.

We all need to appreciate, even celebrate, our heritage. But if we regularly tie our identity to the hitching post of heredity, rather than the rail of current reality, we could forget where we truly live and what’s expected of us. Overemphasizing that someone is an Italian American, Mexican American (Chicano), African American, Asian American, or however it's declared in these days of political correctness, results in more isolation and less assimilation.

I encourage you to explore your heritage, whatever it might be, but be who you are where you are. And if in your searching you find out that we might be distant relatives, let me know.

There's More Where That Came From

03/02/24 11:10

We’re completely content with the simplicity that abounds in our humble hamlet of Plockton. Take, for example, the procurement of groceries. The biggest store in the Highlands is Morrisons in Inverness, two hours and ten minutes northeast by train. There are smaller food co-ops in Kyle of Lochalsh, Broadford, and Portree. But here in our village, the main market is Plockton Shores.

This unassuming shop blends in with the long row of look-alike homes on Harbour Street — all of which were built to house herring fishermen and their families in a former century. Karen (pronounced Kay´-ruen) is Plockton Shores’ primary operative. Her always-bright welcome is a suitable substitute for sunshine on back-to-back days of Scottish mist and opaque skies.

The north side of the establishment is a café that serves homecooked meals and local brews. It’s open for breakfast and lunch this time of year — and dinner when warmer weather and a longer-lingering sun on the craigs lures tourists to town for fabulous photo ops and a loch-side supper.

The south half of the store is where locals buy stamps for the post — the red box is just two doors down — The Daily Record, fresh baked goods, and takeaway tea and coffee. But more than that, the south side’s also the village grocery.

Five steps further inside there’s a fresh produce section where 15 different fruits and vegetables share space in ten wicker bins on the wall. Naturally, you’ll find a neep or two (think rutabaga). You can’t serve haggis without mashed neeps. But the potatoes and leeks are the first to sell out every week as they are the named players in potato-leek soup, a Scottish favorite. (Judi has tried out two recipes so far. One was good enough to give a portion to the pastor to take home when he stopped by for a visit two evenings back.)

On adjacent shelving there are tins (cans) of Cullen Skink, Cock-a Leekie (also made with leeks), and a couple of other soups. You’ll find a few tubes of biscuits (crackers) and some bags of crisps (chips). The bread table has about a dozen loaves when freshly stocked, plus there’s a few sacks of flour underneath for those who’d rather bake their own.

Behind the till is a glass-fronted fridge with a sampling of butter, yogurt, and cheese, plus a pack or two of pork sausage. Squash (diluted juice) and fizzy drinks are kept cold on the bottom shelves. You can always find Coke, craved the world over, and Irn-Bru, a unique soda with popularity that starts to go flat south of Glasgow.

Beer and various household necessities occupy the rest of the shelves in Plockton Shores. If it’s not in stock, you can borrow from a neighbor until the next trip to Kyle.

What’s amazing is that the entire market takes up about 90 square feet!

Before I go on, I would be remiss not to mention auxiliary sustenance sales in our little village. Many of the crofts vend fresh eggs and preserves. You just have to know what lane to walk down, which barn door to enter, and where to leave your pounds. But our favorite food buying experience rolls our way every Wednesday: Yogi’s seafood van. In probably 20 cubic feet of refrigerated space in the back end of his wee lorry he portions out fillets of salmon, haddock, smoked haddock, halibut, hake, and monkfish, plus langoustines and other crustations. He simply blows his horn, and the locals scurry out to the street to see what fish have been freshly caught. Yogi is a grown-up version of the Good Humor man. Instead of a King Cone you get king crab.

I must admit, it's novel to live for a time in this world of reduced options and limited supply. It’s a world away from the mega stores in major cities — even Inverness — where the contents of just the endcap displays in the first two aisles would be more than Plockton Shores’ shelves could hold.

Buying food in our current location certainly makes us appreciate both the incredible variety and sheer volume of commodities that are found where we usually shop. It also reinforces the fact that the having vs. lacking match is always won in the late innings by the latter. We find ourselves paying more attention to our pantry than we do at home, and asking each other what needs to be used up next before it goes bad.

There’s absolutely no question about it: We can very easily adjust and live well on the inventory of local stores here in the Highlands. People all around us have done it for decades. We’re actually quite content. And the generosity of friends is always an added blessing. Even so, the word that that I’m contemplating during this season is abundance. There is scarcity — which we are far from. Then there’s sufficiency — which is where we are. Abundance is what one finds in Inverness or Glasgow or Colorado Springs.

The question I’m pondering: When it comes to God’s spiritual inventory in his storehouse of blessing, am I content with sufficiency even though abundance is always available?

“[God] is able to do exceedingly abundantly above all that we ask or think, according to the power that works in us… (Ephesians 3:20, KJV).

“I have come that they may have life, and that they may have it more abundantly” (John 10:10, KJV).

How many times do we hurry to a corner store for spiritual staples when our Heavenly Father’s supermarket is open ‘round the clock? What’s more, His inventory is infinite. Even when we empty a shelf, there’s always more where that came from.

This unassuming shop blends in with the long row of look-alike homes on Harbour Street — all of which were built to house herring fishermen and their families in a former century. Karen (pronounced Kay´-ruen) is Plockton Shores’ primary operative. Her always-bright welcome is a suitable substitute for sunshine on back-to-back days of Scottish mist and opaque skies.

The north side of the establishment is a café that serves homecooked meals and local brews. It’s open for breakfast and lunch this time of year — and dinner when warmer weather and a longer-lingering sun on the craigs lures tourists to town for fabulous photo ops and a loch-side supper.

The south half of the store is where locals buy stamps for the post — the red box is just two doors down — The Daily Record, fresh baked goods, and takeaway tea and coffee. But more than that, the south side’s also the village grocery.

Five steps further inside there’s a fresh produce section where 15 different fruits and vegetables share space in ten wicker bins on the wall. Naturally, you’ll find a neep or two (think rutabaga). You can’t serve haggis without mashed neeps. But the potatoes and leeks are the first to sell out every week as they are the named players in potato-leek soup, a Scottish favorite. (Judi has tried out two recipes so far. One was good enough to give a portion to the pastor to take home when he stopped by for a visit two evenings back.)

On adjacent shelving there are tins (cans) of Cullen Skink, Cock-a Leekie (also made with leeks), and a couple of other soups. You’ll find a few tubes of biscuits (crackers) and some bags of crisps (chips). The bread table has about a dozen loaves when freshly stocked, plus there’s a few sacks of flour underneath for those who’d rather bake their own.

Behind the till is a glass-fronted fridge with a sampling of butter, yogurt, and cheese, plus a pack or two of pork sausage. Squash (diluted juice) and fizzy drinks are kept cold on the bottom shelves. You can always find Coke, craved the world over, and Irn-Bru, a unique soda with popularity that starts to go flat south of Glasgow.

Beer and various household necessities occupy the rest of the shelves in Plockton Shores. If it’s not in stock, you can borrow from a neighbor until the next trip to Kyle.

What’s amazing is that the entire market takes up about 90 square feet!

Before I go on, I would be remiss not to mention auxiliary sustenance sales in our little village. Many of the crofts vend fresh eggs and preserves. You just have to know what lane to walk down, which barn door to enter, and where to leave your pounds. But our favorite food buying experience rolls our way every Wednesday: Yogi’s seafood van. In probably 20 cubic feet of refrigerated space in the back end of his wee lorry he portions out fillets of salmon, haddock, smoked haddock, halibut, hake, and monkfish, plus langoustines and other crustations. He simply blows his horn, and the locals scurry out to the street to see what fish have been freshly caught. Yogi is a grown-up version of the Good Humor man. Instead of a King Cone you get king crab.

I must admit, it's novel to live for a time in this world of reduced options and limited supply. It’s a world away from the mega stores in major cities — even Inverness — where the contents of just the endcap displays in the first two aisles would be more than Plockton Shores’ shelves could hold.

Buying food in our current location certainly makes us appreciate both the incredible variety and sheer volume of commodities that are found where we usually shop. It also reinforces the fact that the having vs. lacking match is always won in the late innings by the latter. We find ourselves paying more attention to our pantry than we do at home, and asking each other what needs to be used up next before it goes bad.

There’s absolutely no question about it: We can very easily adjust and live well on the inventory of local stores here in the Highlands. People all around us have done it for decades. We’re actually quite content. And the generosity of friends is always an added blessing. Even so, the word that that I’m contemplating during this season is abundance. There is scarcity — which we are far from. Then there’s sufficiency — which is where we are. Abundance is what one finds in Inverness or Glasgow or Colorado Springs.

The question I’m pondering: When it comes to God’s spiritual inventory in his storehouse of blessing, am I content with sufficiency even though abundance is always available?

“[God] is able to do exceedingly abundantly above all that we ask or think, according to the power that works in us… (Ephesians 3:20, KJV).

“I have come that they may have life, and that they may have it more abundantly” (John 10:10, KJV).

How many times do we hurry to a corner store for spiritual staples when our Heavenly Father’s supermarket is open ‘round the clock? What’s more, His inventory is infinite. Even when we empty a shelf, there’s always more where that came from.