Just Another Foreigner

12/02/24 13:34

In any of the many tourist shops in Edinburgh, Glasgow, or Inverness, those of Scottish descent can purchase countless tartan products denoting their clan. If you’re a Stewart, Campbell, Fraser, MacDonald, MacLeod, MacKenzie, or any of the other 30 or more “Macs,” there’s a kilt, scarf, fly or tie in your personal plaid, either on the rack or in the back.

Notwithstanding, in our past visits to Scotland, we’ve never been able to find anything bearing the colors of my mother’s father’s family. They were Scotch-Irish with the surname Gillogly. On those occasions when we inquired about our kin’s woven standard, the shop clerks would always get puzzled looks on their faces and say they were unfamiliar with the name — and then refer us to another shop that had more inventory or a self-avowed genealogy expert.

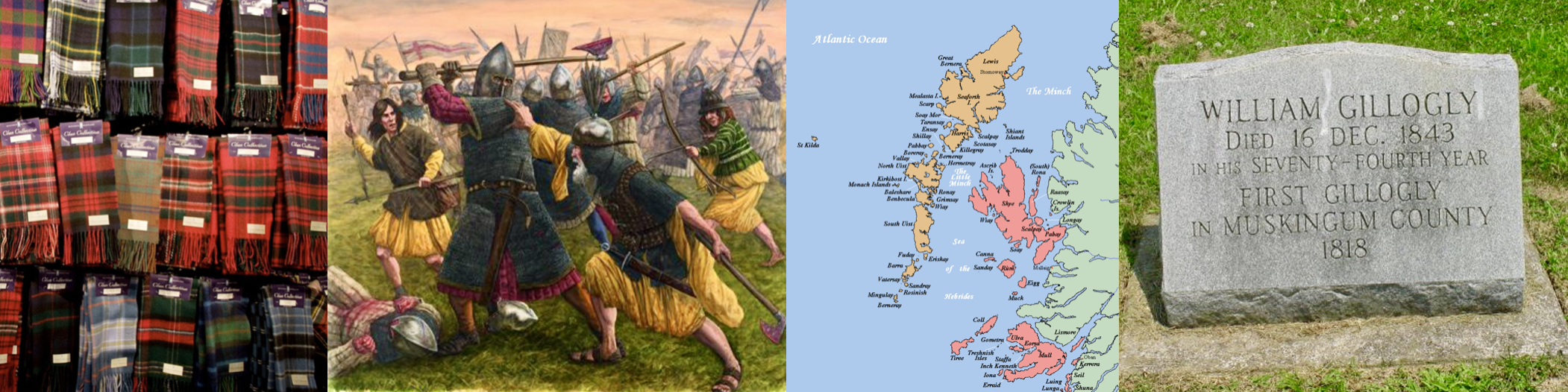

Actually, we didn’t need the latter. My mother’s sister was a genealogy aficionado. Long before the days of the Internet and ancestory.com, she taught college-level courses on lineage research. By spending countless hours in libraries, courthouses, and cemeteries, she traced her father’s ancestors back to Europe in the 17th century. Thanks to her diligence, we knew when, why, and how our people journeyed from Ireland to the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia to the mountains of western Pennsylvania to the hills of southeastern Ohio. In the “old country,” they were farmers who worked the land on several islands in Lower Lough Erne, near Enniskillen, in County Fermanagh, Ulster. My fifth great-grandparents, John and Mary Jane (Moore) Gillogly were both born in Enniskillen in 1847 but died in Muskingum County Ohio, she in 1816 and he in 1855 — yes, he lived to be 108.

But what about the Scottish origin, and what took them to Ireland? Starting in the early 1600s, Scottish protestants living largely in Dunfries and The Borders, the southernmost parts of the country, were coerced, even forced, to leave their homes and move west across the water to populate the Plantation of Ulster so England would have a foothold in Ireland. Those peasant pawns were the first to be known as Scotch-Irish. The English plan was to confiscate all the lands of Gaelic Irish nobility and set the Scots up as farmers on those same properties. But the farmers weren’t fighters. For this plan to work, they needed enforcers. So London looked north and decided the rascally, rugged Highlanders who had been giving them fits since the days of William Wallace were who they needed to hire.

But what’s interesting is that many Highland warriors were already in Ireland — recruited hundreds of years earlier to comprise private armies for Irish chieftains. The irony is that by the 1600s, you had Highlanders protecting the Irish from Highlanders serving as soldiers for the English. Whenever my relatives got to Ireland — probably in the 1200s or 1300s — and whatever side they were on — probably the Irish — they were apparently mercenaries. As a neighbor here in Plockton told me, “Highlanders don’t need much of a reason to fight.”

But why no personalized plaid? What I recently learned was that Gillogly was an Anglicized forms of the Irish surname Galloglaigh, which was an Irish variant of the Gaelic name MacGalloglach. In Gaelic, the mac, of course, means “son of.” The gall part means “foreigner” and oglach (or owglass) means young warrior. Pushing this historical door open a bit further, it seems my Scottish ancestors were heavily armed fighters referred to as Gaelic-Norse who originally rowed over from the Skrettingland area of southeast Norway. Essentially, they were Viking marauders and plunderers who liked what they saw in Scotland and decided not to row back. But instead of being known by their family, they were known by their macabre profession, and thus there was no family crest or tartan. However, the Scottish home base for the MacGalloglach clan was the Balmartin area of North Uist in the Outer Hebrides, Scotland’s far northwestern islands. That means they would have been intermingled and probably intermarried with the Clan MacDonald who laid hold to that land early on. Now that I know, I guess the closest I’ll ever get to a Gillogly tartan, is a MacDonald hand-me-down.

In Act 1, Scene 2 of Shakespeare’s Macbeth, an unnamed wounded soldier tells King Duncan and his sons, “…the merciless Macdonwald....from the Western Isles of kerns and gallowglasses is supplied.” In other words, the MacDonalds had military might at their disposal: the Kerns, lightly armed foot soldiers who generally carried a wooden shield and a sword; and the Gallowglass (a.k.a., Galloglachs… Galloglaighs…Gilloglys), heavily armored warriors hand-picked for their strength and massive size. They were known for carrying halberds, which were battle axes on long poles. Thankfully, they eventually beat their weapons into farming tools and took a more peaceful path forward — although I have a couple of cousins…never mind.

It's been fun to find from whence my family came. But after having a three-day dalliance with days-of-old, two things jump out at me. The first is that we are all foreigners — every one of us. A few centuries here, and few centuries there, but humanity is constantly on the move — and often bloodshed follows. Perhaps we’ve learned our lesson over time and welcoming the stranger in the days ahead will be an art that we finally and peacefully perfect. Actually, I think Christians have a mandate to do so. See Romans 15:1-6.

The second thing is that we are who we are where we are. It’s been fun to romanticize about having Highland roots. We love being part of the local culture here in Scotland, and Judi will probably start making potato-leek soup when we get back to Colorado. (Her mother’s family is also Scotch-Irish.) But the truth is, I could wrap on a kilt and chase the deer on Sgùrr Alasdair all day long, but I’m not a Highlander any more than I’m a Viking voyager or an Irish cottier.

We all need to appreciate, even celebrate, our heritage. But if we regularly tie our identity to the hitching post of heredity, rather than the rail of current reality, we could forget where we truly live and what’s expected of us. Overemphasizing that someone is an Italian American, Mexican American (Chicano), African American, Asian American, or however it's declared in these days of political correctness, results in more isolation and less assimilation.

I encourage you to explore your heritage, whatever it might be, but be who you are where you are. And if in your searching you find out that we might be distant relatives, let me know.

Notwithstanding, in our past visits to Scotland, we’ve never been able to find anything bearing the colors of my mother’s father’s family. They were Scotch-Irish with the surname Gillogly. On those occasions when we inquired about our kin’s woven standard, the shop clerks would always get puzzled looks on their faces and say they were unfamiliar with the name — and then refer us to another shop that had more inventory or a self-avowed genealogy expert.

Actually, we didn’t need the latter. My mother’s sister was a genealogy aficionado. Long before the days of the Internet and ancestory.com, she taught college-level courses on lineage research. By spending countless hours in libraries, courthouses, and cemeteries, she traced her father’s ancestors back to Europe in the 17th century. Thanks to her diligence, we knew when, why, and how our people journeyed from Ireland to the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia to the mountains of western Pennsylvania to the hills of southeastern Ohio. In the “old country,” they were farmers who worked the land on several islands in Lower Lough Erne, near Enniskillen, in County Fermanagh, Ulster. My fifth great-grandparents, John and Mary Jane (Moore) Gillogly were both born in Enniskillen in 1847 but died in Muskingum County Ohio, she in 1816 and he in 1855 — yes, he lived to be 108.

But what about the Scottish origin, and what took them to Ireland? Starting in the early 1600s, Scottish protestants living largely in Dunfries and The Borders, the southernmost parts of the country, were coerced, even forced, to leave their homes and move west across the water to populate the Plantation of Ulster so England would have a foothold in Ireland. Those peasant pawns were the first to be known as Scotch-Irish. The English plan was to confiscate all the lands of Gaelic Irish nobility and set the Scots up as farmers on those same properties. But the farmers weren’t fighters. For this plan to work, they needed enforcers. So London looked north and decided the rascally, rugged Highlanders who had been giving them fits since the days of William Wallace were who they needed to hire.

But what’s interesting is that many Highland warriors were already in Ireland — recruited hundreds of years earlier to comprise private armies for Irish chieftains. The irony is that by the 1600s, you had Highlanders protecting the Irish from Highlanders serving as soldiers for the English. Whenever my relatives got to Ireland — probably in the 1200s or 1300s — and whatever side they were on — probably the Irish — they were apparently mercenaries. As a neighbor here in Plockton told me, “Highlanders don’t need much of a reason to fight.”

But why no personalized plaid? What I recently learned was that Gillogly was an Anglicized forms of the Irish surname Galloglaigh, which was an Irish variant of the Gaelic name MacGalloglach. In Gaelic, the mac, of course, means “son of.” The gall part means “foreigner” and oglach (or owglass) means young warrior. Pushing this historical door open a bit further, it seems my Scottish ancestors were heavily armed fighters referred to as Gaelic-Norse who originally rowed over from the Skrettingland area of southeast Norway. Essentially, they were Viking marauders and plunderers who liked what they saw in Scotland and decided not to row back. But instead of being known by their family, they were known by their macabre profession, and thus there was no family crest or tartan. However, the Scottish home base for the MacGalloglach clan was the Balmartin area of North Uist in the Outer Hebrides, Scotland’s far northwestern islands. That means they would have been intermingled and probably intermarried with the Clan MacDonald who laid hold to that land early on. Now that I know, I guess the closest I’ll ever get to a Gillogly tartan, is a MacDonald hand-me-down.

In Act 1, Scene 2 of Shakespeare’s Macbeth, an unnamed wounded soldier tells King Duncan and his sons, “…the merciless Macdonwald....from the Western Isles of kerns and gallowglasses is supplied.” In other words, the MacDonalds had military might at their disposal: the Kerns, lightly armed foot soldiers who generally carried a wooden shield and a sword; and the Gallowglass (a.k.a., Galloglachs… Galloglaighs…Gilloglys), heavily armored warriors hand-picked for their strength and massive size. They were known for carrying halberds, which were battle axes on long poles. Thankfully, they eventually beat their weapons into farming tools and took a more peaceful path forward — although I have a couple of cousins…never mind.

It's been fun to find from whence my family came. But after having a three-day dalliance with days-of-old, two things jump out at me. The first is that we are all foreigners — every one of us. A few centuries here, and few centuries there, but humanity is constantly on the move — and often bloodshed follows. Perhaps we’ve learned our lesson over time and welcoming the stranger in the days ahead will be an art that we finally and peacefully perfect. Actually, I think Christians have a mandate to do so. See Romans 15:1-6.

The second thing is that we are who we are where we are. It’s been fun to romanticize about having Highland roots. We love being part of the local culture here in Scotland, and Judi will probably start making potato-leek soup when we get back to Colorado. (Her mother’s family is also Scotch-Irish.) But the truth is, I could wrap on a kilt and chase the deer on Sgùrr Alasdair all day long, but I’m not a Highlander any more than I’m a Viking voyager or an Irish cottier.

We all need to appreciate, even celebrate, our heritage. But if we regularly tie our identity to the hitching post of heredity, rather than the rail of current reality, we could forget where we truly live and what’s expected of us. Overemphasizing that someone is an Italian American, Mexican American (Chicano), African American, Asian American, or however it's declared in these days of political correctness, results in more isolation and less assimilation.

I encourage you to explore your heritage, whatever it might be, but be who you are where you are. And if in your searching you find out that we might be distant relatives, let me know.